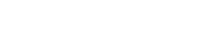

Drones, not aerial ones, but Super Custom-type road delivery vans, have become a darling of security service-men kidnapping young men across the country nowadays.

They bring a chill of fear at every sighting. The unlucky ones who have been arrested and transported to torture chambers in these drones have scary stories to tell about their road experience.

Kakwenza Rukirabashaija, a novelist and human rights activist, has had several run-ins with state agents, rattled by his razor-sharp literary works that are highly critical of the ruling hierarchy. He has been arrested several times, transported in drone vans and brutalized in various detention facilities. Below is one of many testimonies of his torment in and outside of a drone.

On the 18th day of September 2020, I was in bed, sound asleep, when the house manager woke me up with a soft knock on our bedroom door. I checked the time it was exactly 6:15am.

“Yes Anita, what is it?”

“Uncle, there are three men outside who want to talk to you,” said Anita. “Who are they?” asked my wife, in a sleepy voice.

“I do not know them and they are asking for Uncle,” Anita responded.

“Have you opened the gate for them or are they still outside?” asked my wife as she got up to draw the mosquito net.

Anita had sauntered away so she didn’t hear the question posed by my wife. When my wife walked to the bathroom to ease herself, I also got up and reached for the bedroom door. I turned the key, twisted the door knob and opened the door.

When I had opened it half-way, I saw about four men in civilian clothes standing in the corridor facing our bedroom. They were wielding guns. I shut the door immediately and screamed. This provoked a question from my wife in the bathroom. I had just opened my mouth to tell my wife that we had been besieged then the door was kicked open with indescribable impunity.

“You are under arrest. Put on your clothes now and we go,” one officer commanded while pointing his sniper’s gun at me.

He had a brimmed hat on. I stood transfixed and speechless on the carpet in the middle of the bedroom, while my wife stood at the threshold to the bathroom door.

“Is this how you bombard people in their bedrooms while they are still sleeping and you arrest them?” a question finally escaped from my mouth.

I noticed that the man with the brimmed hat was the same operative who had commanded the operation that had spirited me away from my home back in April. The man was short and energetic. He had a big nose perched on his hairless face, two owl eyes and a chubby mouth cracked by dehydration.

The argument between me and the operative of course attracted the attention of his fellow rascals, who now entered the bedroom breathing fire and threatened to take me away naked. I was in my underwear.

“We have spent three days without sleeping, looking for you and here you are teaching us how we should arrest you? Are you an insane, tall man?” the ring leader grumbled.

My wife was dumbstruck. She just watched as the criminals invaded our bedroom and demanded that I dress up. No arrest warrant, no civility, no humanity, only impunity and braggadocio. One officer fished out handcuffs from his pocket and fastened them around my wrists, before ordering me to get out of the bedroom.

“Last time you took my husband when he was well and brought him back when he was almost crippled,” cried my wife.

“Our job is to arrest. We take orders and deliver the suspect. So we do not know about that,” a youthful operative in cheap tight jeans and a faded T-shirt answered in a hoarse voice and with a lot of pomp and an exaggerated sense of self-entitlement. His mouth reeked like pigsty.

I was led out of the bedroom and through the corridor and into the dining room. Here Kakwenza Rukirabashaija we found two men in Uganda People’s Defence Forces uniform standing with a policewoman, all armed to the teeth. Behind them stood our village chairman and his deputy who had, conceivably, been called to witness my arrest.

“Where is your phone and the computer?” the commander of the operation asked, looking at me like I had his kidney. “I remember the last time you came here, you took my computer and phones and up to now you have never brought them back yet I was acquitted of your bogus charges,” I shot back.

“So what do you use to write insulting books and/or maybe communication, Mr. Writer?” Another soldier asked. He was tall and in full combat fatigues. “None of your business,” I shot back.

A white drone vehicle with private number plates had parked outside my gate and the engine was running. I was led into it and commanded to sit between two officers in full combat fatigues who had been left behind and idled around in the rear seat of the car.

The car, which is supposed to carry seven people, carried about eleven – including other officers who had surrounded the house. By 6.30 a.m., the drone was roaring on the tarmac towards Kampala.

“I am thirsty. I need to drink some water please. You have arrested me without my wallet so you have to buy water and give me to drink,” I ordered.

By this time, we had passed Magamaga barracks in Mayuge district. The man in the hat who commanded the operation was driving lazily and in a cowardly manner at 50 kilometres per hour.

“I need drinking water, you guys. Don’t you have ears?” I raised my voice.

Truth is, I was very thirsty. My mouth was dry because I am used to waking up in the morning and guzzle two cups of water infused with fresh and succulent lemon.

“This son of a bitch wants to fill his bladder with water so that we make unnecessary stopovers along the way,” the officer on my right mumbled.

I treated the mumble with equanimity and watched them vapidly joke about my request. The driver, who was also the commander of the operation, made a call and requested money from his bosses on the pretext that they had no fuel and that the suspect was hungry and thirsty and was demanding breakfast.

The money was sent and they withdrew it from Mukono, bought for me a small bottle of water for a thousand shillings, and toothpaste and toothbrush for about two thousand shillings. The rest of the money was shared out amongst themselves – ten thousand shillings each.

“What are the toothpaste and brush for?” I asked when I was handed the package. “Where we are taking you, you will need them,” the youthful operative retorted. “You need it more than I need it, young man because your mouth smells like a latrine,” I sneered.

The man looked like a hooligan picked off the street. His skin was pale and he hid his eyes behind designer sunglasses. At noon or thereabouts, we reached Bweyogerere. The drone snaking in the traffic jam. I was instructed to remove my rimless spectacles so that they could cover my head and face with a beanie.

I did their bidding without hesitation because I knew from past experience that a little distance ahead, they would blindfold me so that I would not be able to see where I was being taken.

As a frequent user of the road, of course, I intuited, from the way the car was moving, that it was headed towards Mbuya Military Barracks. When I alighted from the vehicle, I was met with a five-minute drizzle of sanitiser as if they were spraying a cow in a kraal.

All my clothes got wet with sanitiser. By one in the afternoon, I was seated in the corridor of the Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence, on clean and cold tiles, handcuffed, barefoot and blindfolded with a beanie. I knew that I was headed for another round of torture since I was able, even in my blindfolded state, to recognise the torture chamber in which I had been before.

The harrowing din from the interrogating rooms across scared the hell out of me. I prayed to God to lead me. When I was tapped on the head and asked to get up, I knew it was my turn to be tortured. I was determined to break their eardrums and concrete walls with my shrieks upon being beaten like I had been before.

In fact, my spirit jumped out of my body when we entered the interrogation room and I was welcomed by the same lazy Kikiga accent that I readily recognised from the previous torture.

“Kakwenza, how are the tiles now?” he asked, laughing. “What do you mean, sir?” I asked, full of fear. He came closer to me. I caught a whiff of his cheap street perfume through the thick beanie that covered my face.

“Idiot, you described everything in your latest book. Who taught you how to describe things so perfectly?” He then commanded me to kneel down on the tiles and raise my hands.

“No sir, I am not in good enough health to kneel down. I am still sick from the earlier torture,” I said, foolishly.

In a minute, I had received slaps from every angle, slaps that hit every part of my body from the people who had surrounded me. I capitulated and knelt down. One brute began to incessantly and energetically hit the soles of my feet with a baton and another whacked me on the head until I lost control and fell down on the tiles.

“Now you are going to do fifty push-ups,” he commanded. Note that I was still handcuffed. I tried to make a few and failed. When I requested that they remove the handcuffs so that I could do as they commanded, I was instead kicked and I fell down in a heap.

“Let him sit on the chair and tell us about this book,” a voice with a Luo accent said. I was led to a chair where I got ensconced, facing the interrogators. I could feel the presence of some of them behind my back; and they seemed ready to hit me unmercifully.

My tormentors had acquired the soft copy of my manuscript and they began to read for me the introductory poem to the book, written by Kagayi Ngobi, entitled ‘THESE PEOPLE’. I was asked to explain who ‘these people’ are and I spoke the truth – that they are the people in power.

I received hot slaps on the cheeks for about two minutes running. We moved on to the epilogue of the book. I was tasked to explain why I have to involve (President) Museveni in everything I write.

I told them that since Museveni heads the state called Uganda, he is responsible for all the mess we are entangled in since he said that the problem with Africa are leaders who overstay in power, and he has been president since 1986.

I also said Mr. Museveni said he would not preside over a country where someone is arrested and tortured for expressing their views. However, contrary to this commitment on the president’s part, when I wrote a political work of fiction, I was picked up and tortured to near-death.

When I got well, I felt compelled to narrate my ordeal. But again, I had been arrested because I had bled ink and documented the state’s impunity in a book. “We like you, Kakwenza for speaking the truth. So, do you want the president to step aside so that you become the president or are you just making noise?” they asked.

“Leadership comes with responsibility to speak the truth and to stand by your promises. Your boss Museveni has failed

in all so he no longer has the credentials to continue leading our country,” I retorted.

“Your country? You and who?” they asked. “It’s my obligation to be a responsible citizen of this country and by doing so I have to make sure that my country is led well and in the right direction,” I confidently said and waited for clubs and slaps to hit me on the head.

“OK, now about the title of your book. How did you come up with it?” they asked. “I got it from my head,” I answered. “Banana republic where writing is treasonous… why not Banana Republic where writing subversive literature is treasonous?” they asked.

“Sirs, I have never written subversive literature. Whatever I have been writing is nothing but the truth. Bravely enough, I have written when you my tormentors are still around so that you can read it and say this man is not a liar. So, you would not really take me seriously if you read about what you did to me while I’m in exile or when your bosses have been catapulted from power,” I said.

“We wish you good luck in all your plans to catapult the government or perhaps in your next book about this arrest,” they said, laughing.

“Are you going to write another book and narrate that this time we treated you nicely, or…?” I didn’t answer the question. I was told to get out of the room by crawling like a lizard though my face was covered and I couldn’t see the way.At six in the eventide or thereabouts,

I was bundled into a double cabin pick-up and sat down between two officers in full combat fatigues, before the vehicle roared into life and sped out of the barracks. I was still handcuffed and my face still covered with the beanie.

The two warm officers between whom I was ensconced smelt like the inside of a tobacco barn. It was a cold evening and the vehicle waded through the jam outside the barracks. For a moment I thought I was being taken back home.

I was wrong. The brutes were taking me to the Special Investigations Unit in Kireka, where I spent Friday, Saturday, Sunday and Monday until I was given police bond with a proviso that I must report there every Monday of the week.

Imagine such financial harassment and impingement on my liberty of driving 240km every week to report to SIU. Kakwenza Rukirabashaija is a novelist and human rights activist.

Written by KAKWENZA RUKIRABASHAIJA

kakwenzarukirabashaija@gmail.com