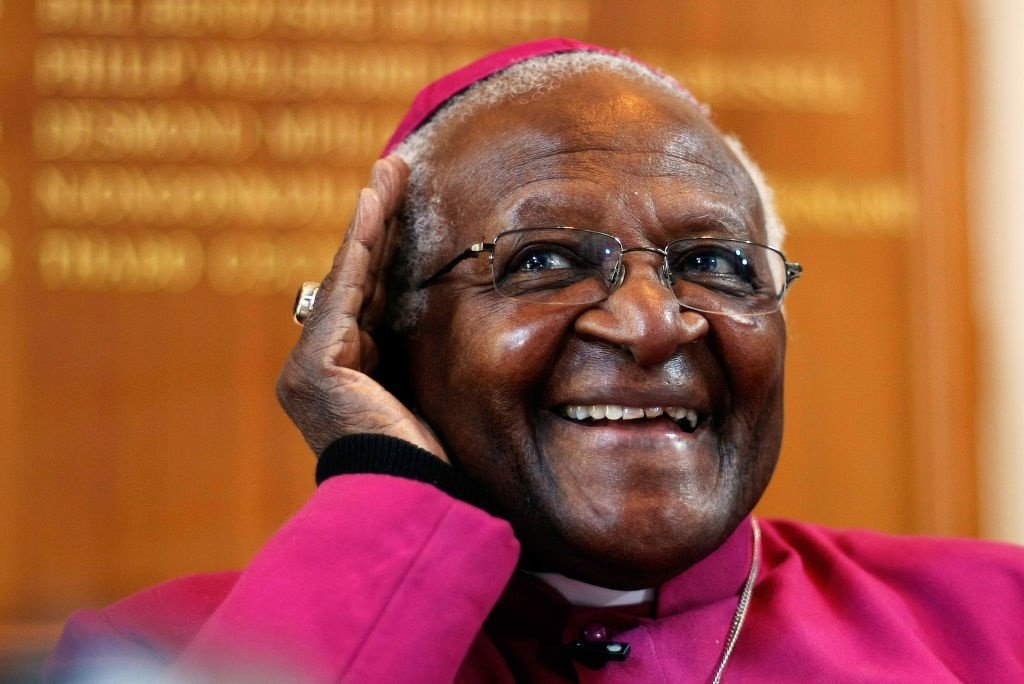

Archbishop Desmond Tutu built a lifelong reputation for championing underdogs and challenging the status quo on issues like race, homosexuality and religious doctrine.

Towards the end of his life, he began a new campaign in support of the assisted dying movement — a hugely sensitive subject in his Anglican Church.

“I have prepared for my death and have made it clear that I do not wish to be kept alive at all costs,” he said in an opinion piece in The Washington Post in 2016.

At the time, he was in and out of hospital for a recurring infection linked to prostate cancer, an illness he was diagnosed with in 1997.

“Dying people should have the right to choose how and when they leave Mother Earth,” he wrote.

‘I wouldn’t mind’

The Nobel laureate’s outspoken editorial propelled the issue to the forefront of public debate and challenged the Anglican Communion’s position on the emotionally charged subject.

Only a handful of countries allow some form of voluntary euthanasia, where a doctor helps the patient to die, or assisted dying, where a terminally ill individual ends their own lives.

In South Africa, euthanasia is a crime punishable by 14 years in jail, though no such sentence has ever been handed down.

South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal last year blocked a bid by a man with prostate cancer to secure the right to a medically assisted death, which could have opened the way to legalise voluntary euthanasia.

The Church of England still opposes assisted dying, stating in 2015 that if it was legalised in the UK it “would allow individuals to participate actively in ending others’ lives, in effect agreeing that their lives are of no further value”.

“This is not the way forward for a compassionate and caring society,” the Church said.

The Anglican Church in South Africa refused to comment on the issue when contacted by AFP.

Before his landmark intervention, Tutu had previously on the issue of assisted dying: “I would say I wouldn’t mind.”

In a 2014 article for Britain’s Guardian newspaper, he chided those around former president Nelson Mandela who had sought to keep him alive. Mandela died aged 95.

“What was done to Madiba was disgraceful,” Tutu wrote, using Mandela’s honorific name.

“There was that occasion when Madiba was televised with political leaders… You could see Madiba was not fully there… It was an affront to Madiba’s dignity.”

Right-to-die activists heralded Tutu’s 2016 article as a game-changer in their fight for assisted suicide to be legalised and ultimately de-stigmatised.

‘A courageous effort’

Sean Davison, the director of assisted dying campaign group Dignity South Africa, told AFP: “When Tutu speaks, the world listens… Maybe this is something we should be talking about rather than closing the discussion completely.”

Even some senior religious figures praised him for stoking debate on an issue that has sharply divided the clerical establishment.

“The archbishop has done a wonderful service to us,” said Father Anthony Egan, a Jesuit priest and lecturer at South Africa’s Wits University.

“It is a courageous effort to try to provoke theologians and Church leaders to think about it.”

But Tutu’s controversial stand on the issue did not receive universal support.

“It is not an enormous surprise that he would come out in favour of euthanasia if he is contradictory about other issues,” said Philip Rosenthal of Euthanasia Exposed, which campaigns against the decriminalisation of assisted dying.

“He has views that are very different to the teaching of the Bible and to the majority of South Africans.”

Liz Gwyther of the Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa said that even the sickest patients could still be made comfortable at the end of their lives.

“We know that with palliative care, it is possible to have a good quality of life with physical comfort and dignity until the end of a natural life,” she said.

“Many people… change their minds (about assisted dying) when receiving palliative care.”

The debate around assisted dying will continue to rage after Tutu’s death, but his intervention helped to lift the taboo that had long surrounded the divisive, emotive subject.

BY AFP