The survivors of deadly Thalidomide disaster in Uganda have taken a bold stance, seeking compensation from the British and German governments.

These Victims are members of the Thalidomide Survivors Uganda association, representing People With Disabilities (PWDs), have petitioned Uganda’s Prime Minister, Hon. Robbinah Nabbanja, urging her intervention in their quest for justice.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the devastating effects of thalidomide manifested globally, affecting over 10,000 children across 46 nations, Uganda included. This drug, initially heralded as a medical breakthrough, was developed by the German pharmaceutical company Grunenthal and licensed in the United Kingdom in 1958. However, its catastrophic side effects led to a ban in 1961.

While compensation was provided to victims in several countries, Ugandan survivors have been overlooked, denied any form of reparation.

Faced with this stark reality, Thalidomide survivors in Uganda have turned to the corridors of power, seeking recourse through the Prime Minister’s Office and other relevant ministries. However, their efforts have often met with frustration and deadlock.

In their petition to Prime Minister Nabbanja, dated August 1, 2023, the survivors outline their grievances and demands. They call for a meeting with the Ambassadors of the United Kingdom and Germany to elucidate the plight of Thalidomide survivors in Uganda and to establish mechanisms for compensation, consistent with international law and recognized organizations like the Contigern Act and the British Thalidomide Trust.

Furthermore, they request the establishment of direct communication channels between the Prime Minister’s Office and the British and German embassies, emphasizing the urgency of addressing the stigma, indignity, and injustices faced by Thalidomide survivors.

Additionally, the survivors seek collaboration with various government authorities, including the police, Resident District Commissioners (RDCs), District Health Officials, and the People With Disabilities in Uganda (PWDU), to compile a comprehensive list of eligible beneficiaries for compensation.

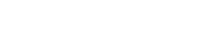

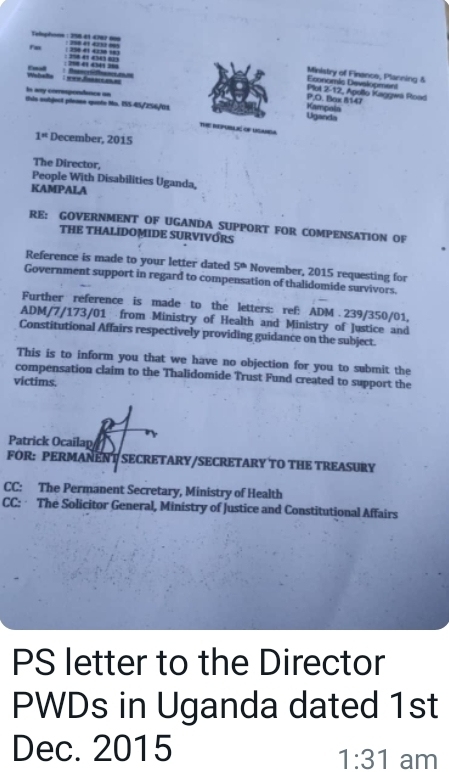

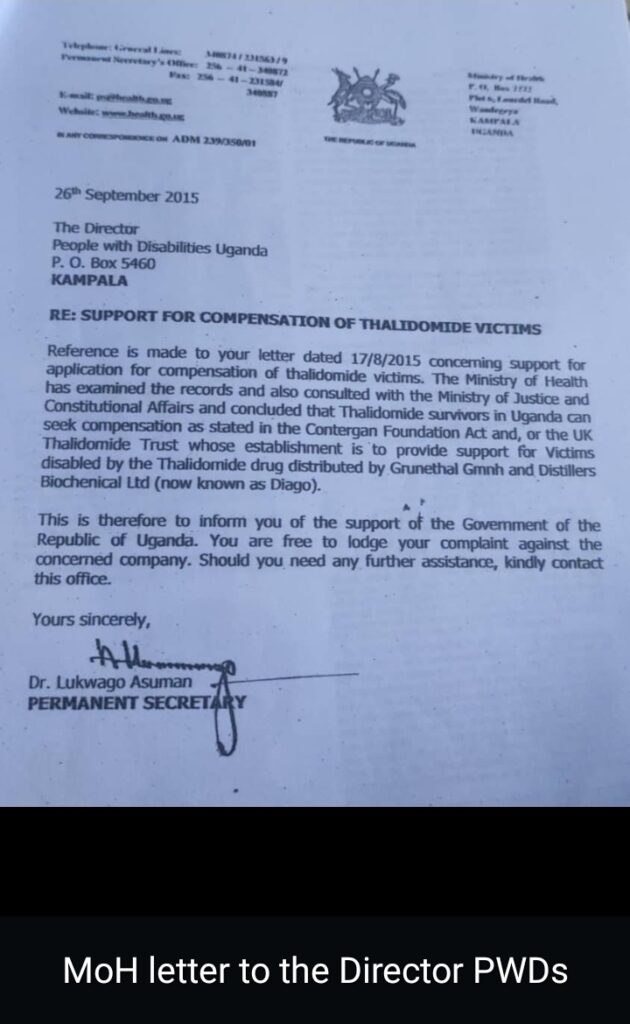

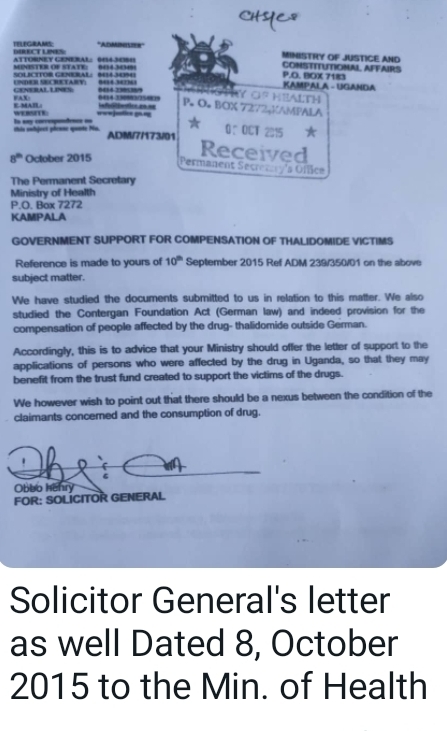

Notably, the survivors highlight previous attempts to raise awareness of their plight, citing correspondences with the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, the Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, and the Ministry of Health. Despite initial support, these efforts have languished without follow-up, prompting the survivors to escalate their appeal to the highest echelons of government.

In their relentless pursuit of justice, Thalidomide survivors in Uganda refuse to be silenced. Their struggle is a poignant reminder of the enduring impact of past injustices and the urgent need for accountability and restitution.

Background Of Thalidomide Catastrophe

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, more than 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities, such as phocomelia, as a consequence of their mothers using the drug thalidomide. Thalidomide was developed by the German pharmaceutical company Grunenthal.

In 1961, news linking the use of thalidomide and horrible birth defects surfaced in England, Germany, and Australia.

Thalidomide had been licensed in the United Kingdom in 1958 and was withdrawn in 1961. It was impossible to know how many pregnant women had been given the drug to help alleviate morning sickness or as a sedative.

Victims of the drug have missing, shortened upper limbs, shortened or malformed lower limbs, eye, ear, and facial damage, and malformations of internal organs.

As a result, Foundations and Trusts were established in Britain, Germany, and other European countries to compensate victims.

In 1973 the Thalidomide Trust was originally established in Britain by both Distillers and the British Government as part of the settlement between Distillers Biochemicals Ltd and Thalidomide survivors.

In 1972, the Contergan Foundation for Disabled People (Contergan Foundation) was established as a federal German foundation under public law. In 2013 the German government enacted the Contergan Foundation Act to assist disabled victims of thalidomide.

Thalidomide was available in Uganda in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when it was marketed worldwide as a non-addictive sedative. Several women who had taken the drugs during pregnancy gave birth to children with a range of severe deformities such as phocomelia.

In 1962, Mulago Hospital doctors published an alert in the British Medical Journal regarding an increase in phocomelia cases in Ugandan newborns. The letter was written to send a message to Ugandans about public health concerns and negative incidents.

At the same time, the medical community in the United Kingdom was warned. Other countries had reported unusual birth abnormalities of this type.

The Ugandan victims were considered “monsters” and were left without support. Many of their peers with similar deformities were identified as Thalidomide victims and received financial support and compensation.

Ugandan survivors in UK have been paid a lump sum as their British counterparts.

But the forgotten survivors in Uganda are suffering from the same health needs and they too require lump sum payments to compensate for previous underinvestment in their health needs.

In other countries, Thalidomide survivors have been paid a lump sum when they are first recognized.

In Canada and Germany this has been recognized as payment to compensate for previous underinvestment in their health needs. In Belgium, a lump sum was provided as compensation for pain and suffering.

Following the revelation of the Thalidomide catastrophe the Thalidomide Survivors in Uganda were abandoned without appropriate support to manage their complex healthcare and disability support needs.

The victims were born with significant deformities of the limbs, eyes, and ears, as well as less visible internal deformities, including significant organ and nerve damage, with no pattern of family history.

Neither doctors nor the survivors’ families could explain the cause of their developmental problems. They were unaware that their injuries were related to Thalidomide.

Before the Thalidomide crisis in Uganda, drug safety had not been explored. Many more undiagnosed Thalidomide victims may exist, according to medical discoveries.

However, it is important to note that the biggest dilemma they face is that whenever they approach the government of Uganda for support, they are informed that Thalidomide was administered in Uganda by the British colonial government, not the Ugandan government, which took over power after independence.

This is because to date, the Ugandan Government has not accepted that it played a role in the Thalidomide tragedy.

For more than 60 years, the Ugandan Government has left Thalidomide survivors without support and has maintained that Uganda’s constitutional arrangements, as they were understood at the time, mean that the Uganda Government should not be held responsible for the Thalidomide tragedy.