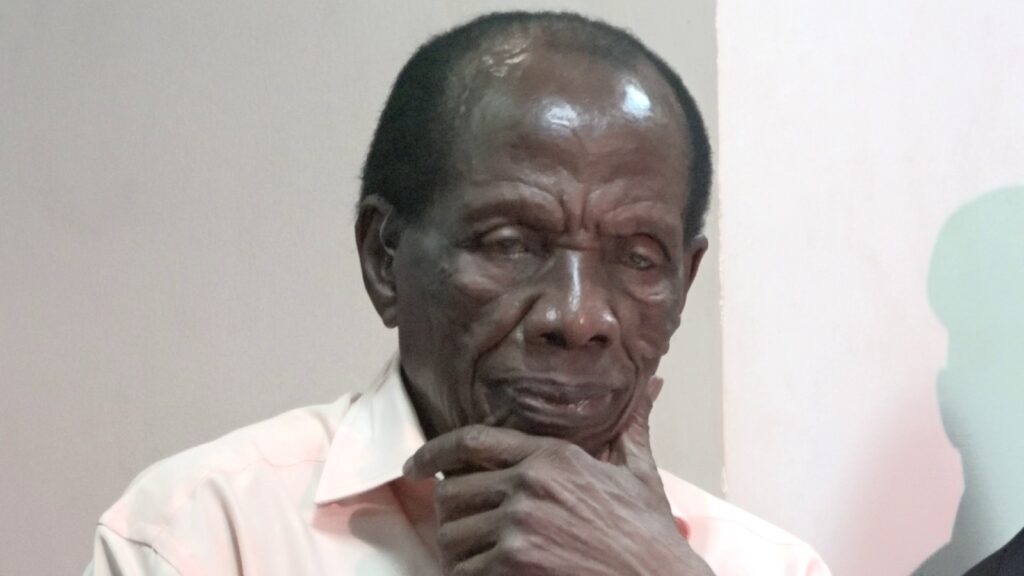

He always said, “Justice delayed is justice denied.” This sentiment rings especially true in the case of one of Uganda’s first Muslim doctors, Muhammed Buwule Kasasa, who passed away before seeing the resolution of his lengthy land dispute with Mengo.

Muhammed Buwule Kasasa, a pioneering figure in Uganda’s medical community, had a longstanding legal battle over 640 acres of land in the suburb of Mutungo.

He had won his case against the estate of Sir Edward Mutesa II, the former King of Buganda. However, the protracted litigation, initiated 21 years ago, was still unresolved at the time of his death.

The Buganda kingdom had filed numerous applications, effectively stalling the final decision.

The administrators of Mutesa II’s estate are Dorothy Nasolo Nalinnya, Sarah Nalinnya Kagere, and Prince David Wassajja.

Despite the Court of Appeal upholding a High Court decision on November 14, 2022, that declared Kasasa as the rightful owner of the land, the Mutesa family did not relent.

They continued to pursue legal avenues to reclaim the land, creating a convoluted legal landscape.

Following petitions from Mengo, the Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) was compelled to deposit UGX 6 billion, meant as compensation for the Mutungo land, into the court.

This action kept the compensation out of Kasasa’s reach pending the case’s resolution. Kasasa, who had reached the age of 90, was battling multiple health issues, including diabetes and hypertension.

Despite his declining health, he remained determined to see justice served.

In February, Kasasa took his grievances to the Judicial Service Commission chairman, Justice Benjamin Kabiito.

He expressed his frustration over the incessant delays in his case, stating, “I am of advanced age, but tragically, judicial officers have made me a victim of gross injustice at the temple of justice. I have witnessed and experienced a cartel or a syndicate scheming to deny me access to my money.”

He further lamented, “The money (UGX 6 billion) was unfairly and irregularly deposited in the High Court by UNRA.

It is difficult to explain why the government agency deposited the money in court. I fear that my money may be stolen unless you intervene.”

Following Kasasa’s death, Judiciary spokesperson James Ereemye Mawanda explained the legal procedures that would follow.

According to the law, the death of a party in a legal matter necessitates that a family member apply for letters of administration to manage the deceased’s estate.

Once these letters are obtained, the appointed person can join the legal proceedings as a representative of the deceased. If they win the case, the awarded compensation will be given to the beneficiaries of the estate.

In 2022, Court of Appeal justices Elizabeth Musoke (now a Supreme Court judge), Christopher Gashirabake, and Eva Luswata concurred with High Court judge Eudes Keitirima’s position regarding the argument made by Kasasa’s counsel, Simon Kiiza.

Kiiza argued that Mutesa’s family, having admitted to losing the land, could not logically claim to recover it.

He invoked the doctrine of approbation and reprobation, which prevents a litigant from adopting inconsistent positions in legal proceedings.

“Mutesa’s family sued to recover land and then filed another suit admitting they had lost the land but sought to recover it. This inconsistent conduct amounts to approbation and reprobation,” Justice Gashirabake ruled. The justices agreed that Mutesa’s family, having acknowledged their loss, could not simultaneously claim to recover the land and seek compensation. Consequently, the court dismissed the appeal filed by Mutesa’s family and awarded costs to Kasasa. The justices observed that pursuing a trial for the recovery of land already admitted to be lost would be futile.

Court documents provide further context to this convoluted case. In 1966, Mutesa II, exiled in Britain, granted his sister, Princess Victoria Mpologoma, powers of attorney to act on his behalf.

In 1968, Mpologoma sold the land to Masaka tycoon Benjamin Kwemalamala Kintu. Kintu subsequently sold the land to Lake View Properties Limited, which mortgaged the property to Barclays Bank (now Absa) in 1972.

When Lake View Properties defaulted, Kasasa stepped in, paid off the debt, and acquired the land titles. The land was officially transferred to him on November 6, 1979.

Kasasa’s death adds a poignant chapter to this long-standing legal saga. His struggle underscores the critical need for judicial efficiency and integrity, echoing his belief that “justice delayed is justice denied.”

The resolution of this case now rests in the hands of his heirs, who must navigate the legal system to finally secure the justice and compensation he fought for until his last days.